The recent assassination of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in an Israeli airstrike has led to celebrations in Syria’s Idlib region. For many Syrians who have endured the terror of Nasrallah’s forces, this moment represents a long-awaited sense of relief. However, the celebrations and their international attention has also revealed a stark and painful double standard that has haunted the Syrian conflict for over a decade—the unequal value placed on Syrian lives compared to others in the region.

Hezbollah’s intervention in the Syrian civil war was pivotal for Assad’s regime, helping him regain control over key provinces and ultimately hold onto power. For many Syrians, particularly in opposition-held areas like Idlib, Hezbollah’s involvement brought not protection but destruction. Nasrallah’s forces are widely seen as enforcers of Assad’s brutality, with their military campaigns responsible for unspeakable violence. The people it killed were not foreign enemies or insurgents; they were civilians, often unaligned with either side.

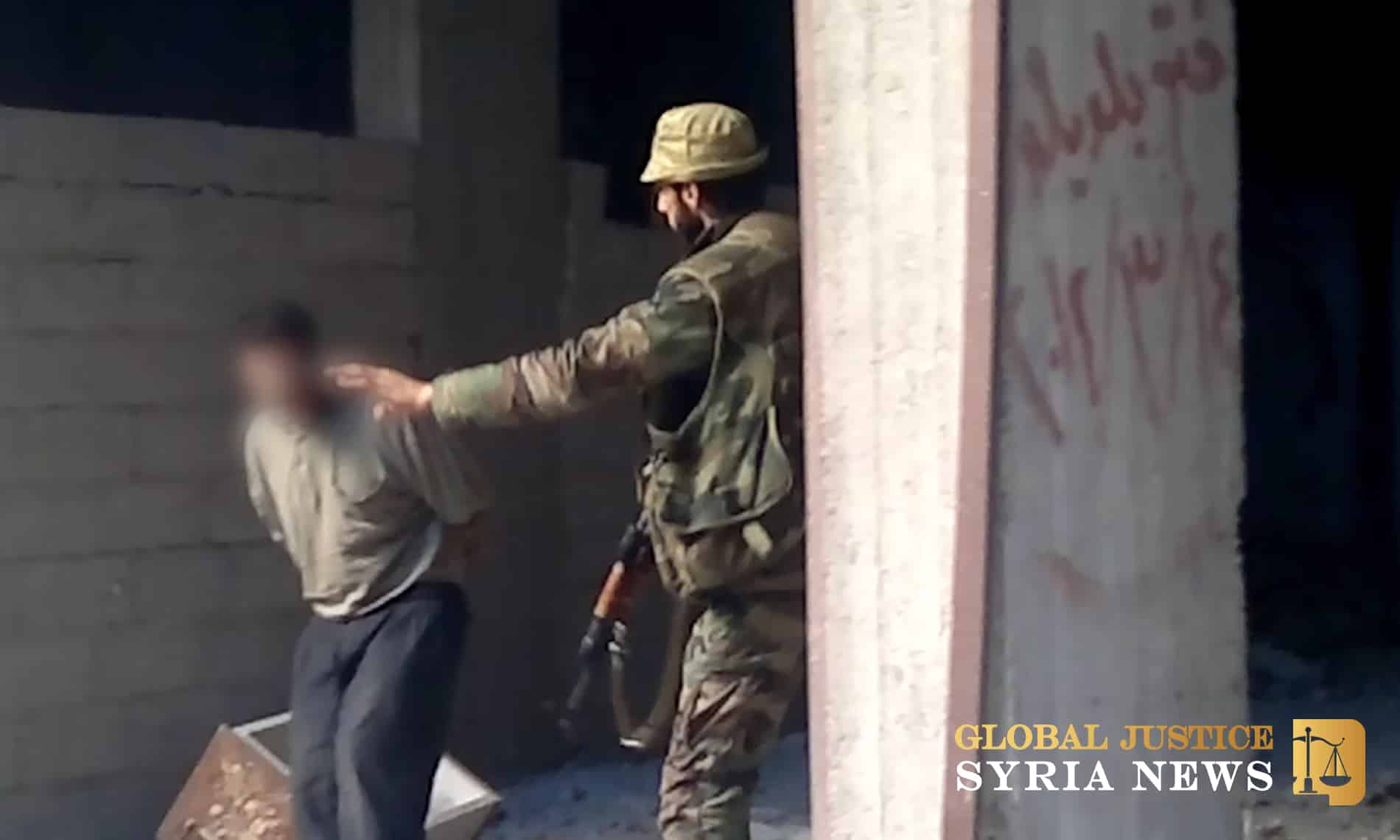

One of the most horrific examples of this violence is the Tadamon Massacre, where at least 250 civilians were brutally executed in broad daylight by pro-Assad forces in a Damascus suburb. The massacre, captured on video, shows detainees being led, blindfolded, to a pit where they were shot and burned. Though the direct perpetrators were members of Assad’s intelligence branch, Hezbollah’s active support for Assad’s regime allowed such atrocities to occur. Hezbollah’s intervention helped reinforce Assad’s ability to wage war against his own people, targeting civilians.

Despite Nasrallah’s death, the international response raises a troubling question: Why is Syrian blood so often treated as less significant?

This is not a new sentiment. Many Syrians have long expressed frustration over the selective outrage and attention given to suffering in the region. While the plight of Palestinians, for instance, rightly garners global solidarity and support, the massacres and crimes committed by Hezbollah in Syria—under the banner of protecting Shia holy sites or resisting Israel—are often ignored or downplayed.

The double standard is glaring. The deaths of Syrians at the hands of Hezbollah, under the tactical approval of Iran, have been met with silence or, worse, justified as part of a broader geopolitical struggle. But when Hezbollah leaders face repercussions, such as Nasrallah’s assassination, the conversation shifts to the implications for regional stability, often ignoring the Syrian bloodshed that preceded it.

The celebrations in Idlib, where people danced in the streets and handed out sweets, reflect a deep sense of vindication and a small glimmer of hope that justice, however delayed, may still be possible. Yet these scenes also highlight the painful reality that for many in the Arab world, the value of life is measured unevenly. Syrians, along with Iraqis and Yemenis, continue to ask why their blood is seen as less precious than that of others in the region.